Eric Oleson as Freud in

Scenes From a Misunderstanding

The plays in these first two volumes, of which seven were performed at the Byrdcliffe Theater in Woodstock, New York, between 2009 and 2013, were inspired in the first instance by an invitation to write a play for the 2009 Jewish Theater Festival in Manhattan. The result was Scenes From A Misunderstanding,a comedy about Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. It was encouragingly received and led to a companion piece, Bad Boy, a matching play rooted instead in contemporary psycho-therapy and written for the excellent Manhattan cast of Misunderstanding. Bad Boy was given a rehearsed reading in Woodstock alongside Scenes From a Misunderstanding, the only one of the plays published here not to be premiered at Woodstock’s Byrdcliffe Theater. The following summer my wife and I formed The Woodstock Players Theater Company to perform the newly written Magus and, the summer after that, Midget In A Catsuit Reciting Spinoza. We continued with three more new plays in the next two years; somehow I had turned into a stage dramatist again, after a long lay-off from the ‘legitimate’ theater, years spent as a novelist, radio dramatist, and scriptwriter. The plays that were now emerging struck me as far more daring than anything I had written during my youthful apprenticeship as a stage playwright in the 1960s, which had taken place in the UK, to what later seemed like premature enthusiasm.

Trey Kay as, Cervantes, Peter Rae as Kafka

Aged 21, I had begun as a stage playwright in the year I graduated from Cambridge, when I was chosen for an ABC Television scholarship that sent me to the Phoenix Theatre, Leicester, for a year of directing plays, followed by a spell of work at ABC. In Leicester I seized the opportunity to stage Dante Kaputt, the comedy I had written in my final year as an undergraduate. The production broke the Phoenix Theatre’s summer attendance record and drew the attention of the National Theatre, who took an option on my future playwriting work and hired me as an assistant director when I had completed my stint at ABC TV’s Teddington studios. In the years that followed I worked on more stage plays, of which one, 26 Efforts At Pornography, was premiered at the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh, performed on BBC television, and staged at the National Theatre . As an apprentice director there, I lurked in the shadow of some of the theatrical titans of the era, including the formidable trio of Sir Tyrone Guthrie, Sir Peter Brook and Sir Laurence Olivier. In a Cottage Hospital, a play I sweated over for several years, was premiered in 1969 at the Traverse Theatre, and, in a separate production that same year, it inaugurated the newly built Stables Theatre in Manchester. More plays followed: Shakespeare Farewell, which was also premiered at the Stables and attracted national attention, and Lovers – overcoming the potential handicap of sharing a name with a play written at the same period by Brian Friel – which was widely performed, abroad as well as in Britain. Thanks to its sponsor, Granada Television, the Stables Theatre assembled a fine company of actors to perform on television the stage plays they premiered in the theatre, where I was the resident dramatist. These had been four turbo-charged years, ’66 to ’69. Looking back I still wonder at the indulgence extended to me.

During the early ’70s a wave of polemical drama spread across British theater, leaving high and dry anyone not given to writing political plays (regardless of how politically engaged outside of theater the author might be, as I was). My preoccupations as a writer were then, and have remained, more existential than overtly political, and for the first time my new play, A Night On The Tor, couldn’t find a home. It had to wait until I staged it myself many years later, at two London venues, followed by a broadcast of the play on BBC radio. But in 1970, with the tide of provocative, crusading plays by contemporaries including David Hare, Howard Brenton and Trevor Griffiths lapping at my feet and leaving me stranded, I was grateful for opportunities to write more television drama scripts. This led to nearly 30 years of screenwriting and scriptwriting, chiefly for the BBC but also for the gamut of regional TV companies, Granada, Thames, Anglia, Yorkshire, Scottish Television, and Southern. In time my yearning to write novels, the oldest and dearest of my writing ambitions, became a reality. Radio drama provided another home, a steadily more lucrative one as German radio stations translated and broadcast new productions of my radio plays for the BBC. Along with TV drama, my output enabled me both to raise a family and make occasional time to pursue novel-writing. Some 17 hours of my writing for television were seen in the U.S. on Masterpiece Theater, including the BBC-2 miniseries, Freud, starring David Suchet. This was a 5-part work that took two years to research and write and formed both the zenith and the nadir of my years as a TV dramatist: the zenith because of what Suchet brought to the series, and the nadir in terms of my own disappointment at the overall production, after so much time expended on the scripts. Freud was well received, especially in the US, but television now felt like an exhausted seam.

The final scene of Midget in a Catsuit Reciting Spinoza.

Penguin Books, and later Viking in the US, brought out Freud, a Novel, a project which enabled me to mine the material anew. The response to subsequent novels, along with the Encore Award from the UK Society of Authors for my second, Richard’s Feet, allowed me to look for visiting Professorships in the US, where yet again the book (which had taken me 12 years to complete) found its most enthusiastic audience. Thanks to this I parlayed successive roles as Visiting Writer at colleges including Cornell and the Universities of Texas, at Austin, and California, at San Diego, into a full-time post at the City University of New York, where I still teach, 17 years on, in the city where I spent childhood years at Manhattan’s French Lycée.

As a child in New York I had watched my parents onstage: my father, Rex Harrison, and my mother, Lilli Palmer, lived a golden period of their marriage and careers with Broadway performances in Maxwell Anderson’s Anne of The Thousand Days, Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra, Ustinov’s The Love of Four Colonels, Christopher Fry’s Venus Observed, and John van Druten’s Bell, Book, and Candle in 1950, when I was 6. Long before My Fair Lady came along when I was 11, I had inhaled theater without realizing it, certainly without realizing that it had caught in my spirit, until I began to stage plays myself at boarding school and at university. There I taught myself directing, on a heady diet of Brecht, Pinter and Shakespeare, before jumping with both feet into writing for the theater of the 1960s. It was an intense but brief involvement, and I never thought it would return. When it did, with the Jewish Theater Festival and Scenes From A Misunderstanding in 2009 – once more exploiting my years of Freud research, this time presenting the material as farce – 40 years fell away at a stroke. I found, as so many have, that once the creative process has been sufficiently engaged it develops according to its own rules, even when this mysterious process continues only in the soul rather than on the page, the stave, or the canvas. When you return to work, it really is as if you’ve never been away; more, it’s as if you’ve been branching off into new forms and with new confidence, in a parallel universe, during the intervening years. With the help of my artist and designer wife, Claire Lambe, the Woodstock Players Theater Company picked up the forty-year slack and abetted a reincarnation. The seven plays in this collection seem to me not only strikingly different from each other, but equally different from the plays I wrote in the 1960s; or maybe not – after reading Midget In A Catsuit Reciting Spinoza, an old friend, the British theater director and former supremo of the Royal National Theatre, Richard Eyre, remarked to my puzzlement that it was written in what was plainly and unmistakably my tone. If so, then for better or for worse I’m the same species of writer I was when I began. Perhaps we always are who we are and, if this is true, then perhaps the encouragement I received in my early years of playwriting wasn’t so much premature as prescient, and I have at last begun to repay the generous enthusiasm of so many years ago.

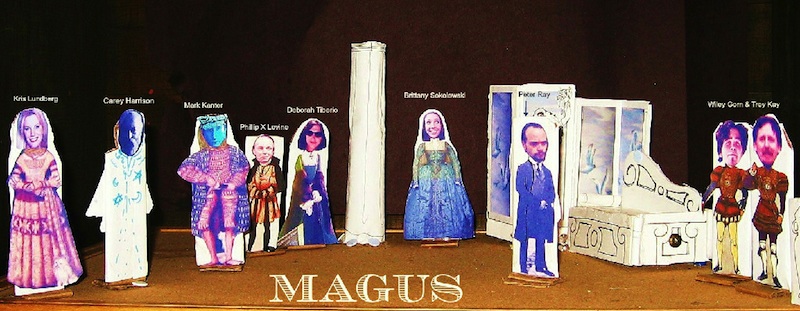

Carey and Phillip X Levine in Magus

Some of the plays in New Plays, Vol. 1, are odd enough bedfellows to need a word of explanation. Like Bad Boy, whose genesis is described above, Magus was written as a companion piece – this time to Edward Einhorn’s play Rudolf II, produced by Edward’s theater company, Untitled Theater Co. no 61, which had staged my Scenes From A Misunderstanding and Bad Boy. The costumes and actors were to be the same as in Rudolf, while taking a different approach to the same time and place in 17th century European history. Cast problems arose, and Magus, under the aegis of the new Woodstock Theater Company, emerged free-standing, without Rudolf. Edward Einhorn’s co-director Henry Akona, who had directed Misunderstanding with great flair, inspired the next play in an email he wrote to me a propos Bad Boy. He said he was going ahead amid unease about directing a love story (new directing territory for him, he maintained), whereas if I had written him a play about, say, a midget in a catsuit reciting Spinoza, he would know just how to begin. I suited my actions to his words. In the event, Henry approved of Midget In A Catsuit Reciting Spinoza, but I was the one who ended up directing it.

Claire Lambe’s preliminary stage and costume designs for Magus

The second volume in this series begins with Hedgerow Specimen, a play born in a fashion not unlike Midget In A Catsuit; and the volume ends with a very different type of play, I Am Your Own For Ever, that at the time of writing this – within a short time of completing it – has as yet no home. Hedgerow Specimen came about as follows. While we were in the midst of rehearsals, one of the actors, Violet Snow, had a dream in which she was appearing in a play of mine. The play even had a name; it was called Hedgerow Specimen. I suited my actions to her dream. Who could resist such a prompting from the unconscious?

Violet Snow as Violet in Hedgerow Specimen

The result, starring Violet, proved to be the best received of the Woodstock Players’ productions, to date. Then Mick O’Brien, who had appeared as Carl Jung in Misunderstanding, as a murderous patient in Bad Boy, and as Salvador Dali and Hitler in Midget, asked me to write a two-person play for himself and me to perform. I made three suggestions: we could be Lenin and Marx meeting each other in a Communist heaven (this might be the title, In Communist Heaven) debating the failure of Communism and who bore most responsibility for this; or we could be Chekhov and Tolstoy, with Tolstoy visiting Chekhov on Chekhov’s farm and telling the younger man frankly how feeble he found Chekhov’s writing to be. (As in reality he did.) Chekhov draws a gun on him. This could be Tolstoy Dies Tonight. Or we could be the older, six-times-married Rex Harrison, grizzled but serene, duking it out with the man whom he saw as having bequeathed him an old age of remorse: the younger Rex Harrison, agonized yet perennially blithe. This was Mick’s choice, and it became Rex & Rex. The final play of the seven, I Won’t Bite You, is set in an interrogation room in a high security South American prison, and it presents the audience with a story-teller whose past consists of extreme experiences, extreme horrors. Tara Dominick, who had originated A Night On The Tor both on stage and on radio, and is the beloved daughter of my no less beloved former co-writer, the late Jeremy Paul, asked for a play. I Won’t Bite You was what demanded to be written, I discovered. In the end it fell to the wonderful American actress Holly Graff, who had played the murderess in Hedgerow Specimen, to premiere it. Where actors are concerned, I have lived and worked under a fortunate star. They are the most generous, most flexible and hardest-working colleagues I have known, and it is to them, no less than to Henry Akona, their inspiration, that these plays are dedicated, in limitless gratitude.

Buy New Plays, Volume 1 on Amazon